Dr. Yang and his Purdue CLA team advance the boundary of sociology by mapping religious practices to explain major cultural changes in the Global East (East Asia)

Dr. Fenggang Yang’s Center on Religion and the Global East is one of the most successful CLA research enterprises. Its projects on religion in China and the Global East have been funded by numerous extramural grants totaling $11.7 million, most recently by a two-million-dollar grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The research aims to expand the discussion about globalization by adding a religious practice dimension in the Global East (East Asian societies, diasporas, and cultures around the globe). The study includes several economic and demographic powerhouses of the Pacific Rim, including Japan, Taiwan, China, and South Korea. The project looks at globalization but also internal structural changes in the target nations through the lens of religious practices. The project’s main goal is to explore an ecological theory of religious change in modernizing societies in East Asia. Religious practices in East Asia seem to, at least in part, buck the trend of secularization found in Western nations. Global East religions changed, and new ones were adopted. Christianity, especially, has seen explosive growth in nations such as South Korea and China. What do the change and growth tell us about religion in general and the future of religiosity in the Global East?

I asked Dr. Yang to discuss these matters in more depth. His answers to my questions speak not only about the main theoretical contribution of his project but also about two important methodological innovations that he brought to the sociology of religion: new survey instruments for measuring religiosity in diverse East Asia societies with broad applicability outside East Asia, and most important spatial and comparative studies of religious organizations using a dedicated platform.

Sorin Adam Matei: What were some of the major or unexpected findings of your recent work on religious behavior in east Asia?

Fenggang Yang: First of all, in East Asia, existing surveys show religious change is volatile, but there is no clear sign of overall decline by most measures of religiosity. Therefore, secularization theories cannot explain religious change in modern East Asia.

Second, the level of religiosity in different societies of East Asia varies substantially when measured with the commonly used survey questions. Moreover, the same survey questions at different times may have dramatically different results. While this may indicate religious change in East Asia is volatile, it may also indicate that the existing measures of religiosity may not capture the actual religiosity or spirituality in East Asia. These commonly used measures have been developed to measure religion in the West, where Christianity is the majority religion in society. However, East Asia has never had a majority religion, while religion is a modern term. most people may not hold an exclusive identity with a particular religion even though they have religious beliefs and engage in religious practices. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new measurements to capture religiosity and spirituality in East Asia more accurately. This is one of the major tasks of my new project.

Third, Christianity has become the most practiced religion among Korean Americans, Chinese Americans, and Japanese Americans. In East Asia, Christianity has become the largest religion in South Korea. According to the Korean Census, 30 percent of Koreans are Christians (Protestants and Catholics). However, in Japan, Christians remain to be around 1 percent of the population. Christians in several Chinese societies (mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, etc.) varies between 5 and 20 percent. My new project is to discover the factors that may explain these variations.

Sorin Adam Matei: A unique feature of your work is the use of maps and mapping to better understand the spread and prevalence of religious practices. What questions were answered by your mapping approach?

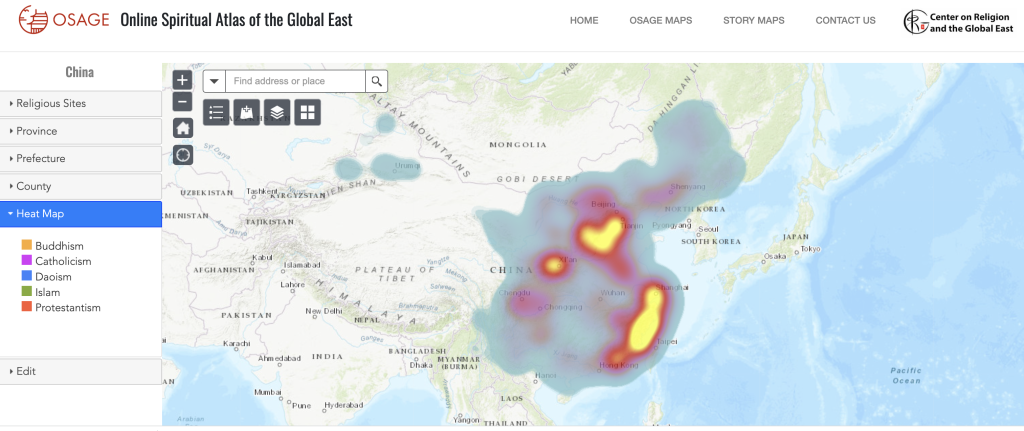

In the classic conceptualization of religion by sociologists, religion is a collective phenomenon. However, most sociological studies of religion nowadays have adopted the individualistic approach and relied on social surveys of individuals about their religious identity, belief, and practices. Religion is a social institution with collective rituals and a moral community. Religious groups are rarely virtual; they occupy a certain space anchored by consecrated place. In other words, they commonly seek a spatial realization of their beliefs. Through consecrating rituals, structured space becomes a sacred center around which people orient themselves. By focusing on religious sites or venues, we turn our attention more to the social, collective nature of religion and examine the inherent spatiality of religious systems. Once the religious sites are mapped, some distribution patterns emerge that otherwise may not be noticed. Many questions can be asked and answered by the mapping approach. For example, once we mapped religious sites based on census data provided by the Statistics Bureau of China, we see that Christianity has become the predominant religion in 11 of the 31 provinces (provincial-level municipalities and ethnic autonomous regions) in China. We can also analyze the “hot spots” or “cold spots” of various religions throughout China. My graduate students and I have also examined the relationship between the spatial distribution of religion and fertility rates or health patterns.

Sorin Adam Matei: East Asia is continuously changing, including in religious terms. What should we expect in terms of religious practices and affiliations to change in the next 20 to 50 years?

As a sociologist, my focus is on the past and the present, which can be examined empirically. On the other hand, once we discover patterns and social factors for past and present religious change, we gain some reasonable ground to project probable change in the future. An interesting question is whether Christian growth in China will be like in South Korea or Taiwan. If it is anywhere near South Korea (almost 30% Christian), China will become the country with the largest Christian population in the coming decades. If the broader social factors remain more or less the same and if the social changes continue the current trend, we should expect dramatic social effects. This change can have earth-shaking consequences not only for China but for the world.

Sorin Adam Matei: Can these practices smoothen some of the geo-strategic tensions in the area?

It is difficult to say. History has shown that religion can be dynamite for domestic politics and international relations. There is a severe lack of social scientific studies of how religion works in society and politics. People tend to hold strong opinions based on personal beliefs and preferences, and scholars turn their heads away from these questions or problems. But, ignoring or neglecting religion-related questions or problems will not lead us to a safer world. If these questions and problems are left only for politicians or religious fanatics, we will head to social destruction. I personally think social scientists and humanities scholars must take on these important questions on religion and do serious scholarship.

You are a sociologist of religion. What is the main contribution of this discipline to understanding human behavior?

Since the founding of sociology as a discipline, classic sociologists such as Emile Durkheim and Max Weber have paid great attention to religion as one of the core social institutions. For Durkheim, religion is the key to understanding social cohesion and social problems such as suicide. For Weber, religion is the key to understanding the modern economic system. Other sociologists or political scientists, such as Alexis de Tocqueville, have argued about the key role of religion in democratization and the modern political system. More recently, Peter Berger examined the religious place or religion-state relations in multiple modernities. Robert Bellah wondered about the necessity of civil religion that may balance the power and the capital in the United States and around the globe.

Following these and many other sociologists, I examine religion at micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. China once experimented with erasing religion from society. During the so-called Cultural Revolution, all religions were banned. Religion, however, survived the ban, lifted after 13 years, and thrived even though China has remained under Communist rule. I have tried to shed light on the reasons for religious survival and revival under Communist rule. Without understanding the religious dynamics, I don’t think we can grasp the profound changes in China’s or East Asia’s economy, politics, and other aspects of social life.

Sorin Adam Matei: What are your plans for research in the Global East?

My current project, “Global East Religiosity and Changing Religious Landscapes,” includes three subprojects: to conduct a survey of religion in East Asian societies, to map religious sites in East Asia and East Asian diasporas, and to carry out comparative historical studies of Christianity in East Asia since 1900. With multiple postdoctoral and graduate researchers and collaborative scholars in East Asia, we will be busy in the next three years.

About Dr. Fenggang Yang

Dr. Yang is an international authority in the sociology of religion, having published tens of peer-reviewed articles and ten books on the emergence of the Religious Global East. He is primarily affiliated with the Sociology Department, with a secondary affiliation in Asian Studies. He was the President of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion (2014-15) and the first President of the East Asian Society for the Scientific Study of Religion (2018-2020). He is the author or editor of several seminal books, such as Atlas of Religion in China: Social and Geographical Contexts (2018), Religion in China: Survival and Revival under Communist Rule (2012), and Chinese Christians in America: Conversion, Assimilation, and Adhesive Identities (1999). His collaborators include Professor Ko-Hsien Su, National Taiwan University, Sakurai Yoshidie, Hokkaido University, and Jae-ryong Song, Kyung Hee University. Among his numerous journal articles, two won distinguished article awards. His media interviews have appeared on the National Public Radio, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Time, Economist, CNN, BBC, etc.

Selected Book Titles by Dr. Yang

Religion in China: Survival and Revival under Communist Rule has been translated into Korean, Italian, Chinese, and Russian

Atlas of Religion in China: Social and Geographical Contexts is