COVID-19: Humanities scholars offer insights for the future by looking at the history of pandemics

Liberal Arts Scholars use humanities perspectives to explain current responses to the COVID-19 crisis

The global COVID-19 pandemic affected us all and demands us all to work toward mitigating its effects. The Purdue College of Liberal Arts intellectual community is ready to step up to the plate. Our scholars are well equipped to propose humanistic responses to the tribulations associated with the pandemic. They are particularly well-positioned to explain how the pandemic challenged “common wisdom” assumptions about “normal” life. They can propose socio-cultural strategies tested by time that may help us make value-driven choices or adopt anxiety coping mechanisms.

We asked two of our leading humanities scholars to help us untangle some of the dilemmas brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic: Dr. Dorsey Armstrong, Professor of Medieval English Literature and the Head of the English Department, and Dr. Paula Leverage, Associate Professor of French and Medieval Studies and the Director of the Center for Neurohumanities. They have studied and have a solid understanding of the Great Plague, which killed between one third and half of the European population between 1347-1350. Their knowledge might help us better understand and respond to the human cultural and social challenges of the pandemic.

The interview was conducted by Dr. Sorin Adam Matei, Professor of Communication and the Associate Dean of Research and Graduate Education.

Dr. Paula Leverage

Dr. Dorsey Armstrong

Dr. Sorin Adam Matei

Dr. Matei: Epidemics tap into some of our deeper fears that go beyond personal harm. They threaten those that are close to us, the livelihood of our community, and ultimately the social support network that makes our lives possible. How did medieval people deal with these fears? What can we learn from their coping mechanisms?

Dr. Armstrong: One thing that is striking about human reactions both then and now is how people tend to freak out in strikingly similar ways. In the Middle Ages, responses to the Black Death ran the whole gamut. Some people turned to religion, hoping to appease God and quell his wrath. The most extreme example of this was the Flagellant movement; these people traveled from town to town, scourging their own flesh with whips and flails in a public display of bodily humiliation and punishment. Their hopes were to save the soul by punishing the flesh, and also to inspire others make similar acts of atonement. Other people, having decided that the end of the world was literally at hand, decided to party away their remaining time on earth, and gave in to licentiousness and debauchery. And although there was no theory of germ transmission, medieval people were smart enough to observe that crowded cities were where the plague spread the quickest, so those who could decamped to the countryside.

Dr. Leverage: Recently, I have been re-reading the work of a fourteenth-century anchorite who survived eight outbreaks of the plague in England. This is the nun Julian of Norwich. Julian comes to mind in answering this question for two reasons. First, as an anchorite quite literally walled into a cell attached to the side of a church, which opened on one side to the public and on the other to the church, Julian counselled local people from a small window overlooking the street. I like to think of her in modern terms as a cross between a spiritual advisor and therapist. In the late 1340s when Julian was a young girl, the plague killed approximately three quarters of the 25, 000 strong population of Norwich. No doubt, the people of Norwich had good reason to come to her with prayer requests and to talk.

The second reason is that Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love is stunningly iconoclastic, and revisionist in her theology, describing not only a God who is a mother, but one who is not vengeful, angry and punishing. Throughout her writing there are messages of hope and comfort, many of which have become well-known, circulating even unattached to their author’s name. For example, in the 16th Revelation, Julian writes, “He said not: ‘You will not be caught up in storms, you will not be overstretched, you will not be made to suffer’ ; but he said : ‘You will not be overcome.’ ” So, in summary, from Julian, the medieval therapist and mystic, I think we can learn that people need people to talk to, and sometimes quiet time to reflect.

Quite coincidentally, I grew up in Norwich and went to a high school which was within short walking distance of Julian’s cell and church.

Dr. Matei: The Black Death pandemic (1347-1350), which culled between one third to a full half of the European population, brought with it many social changes. Only a few, such early forms of social distancing, at times imposed brutally by shuttering houses or blocks, were of medical importance. Can you recount some of the non-medical social changes created by medieval epidemics? How did they change the face of Europe?

Dr. Armstrong: For one thing, the rigid, hierarchical social structure known as the Three Estates (those who fight—the nobles—those who pray—the clergy—and those who work—everyone else) began to break down. Prior to the outbreak of plague, there was a serious land-crunch, and peasants (about 90 percent of the population) were bound to the manor on which they lived and worked and the lord who ruled it. After the Black Death, there was a labor shortage. Nobles started having to pay cash wages to laborers, and labor was in such high demand, that peasants could simply leave and go on down the road to a nobleman who was willing to offer a better deal. Almost everyone who made it to 1353 was better off financially and in terms of land/assets–except the nobility. For the first time, the nobles married down into the merchant class, which actually had money; the merchants were thrilled to have their children marry UP in society and gain titles. This resulted in greater social mobility and opportunities for advancement among the lower classes. For a time the upper classes tried to hold on their power and status—freezing wages at pre-plague levels, limiting movement through the countryside, etc—but a number of revolts against these laws (most notably the English Peasants’ Revolt of 1381) proved that there was no going back to the way things were.

Dr. Leverage: Obviously the depopulation of Europe impacted the workforce significantly, and created a situation which one might expect to benefit the lowest wage earners. But the medieval manorial system, supported by the guilds, controlled workers through legislation which permitted fixing wages, and restricting movement. The consequence of the enforcement of this legislation led to widespread peasant revolt. More generally, we see a questioning and challenging of institutional authority, whether ecclesiastical, or secular, which by the end of the Middle Ages culminates in rent-paying tenants replacing peasant labor, women mystics raising independent voices from anchorages, and ultimately the Reformation.

Dr. Matei: Can we expect any societal changes of the same kind coming out of the COVID-19 crisis?

Dr. Armstrong: What this pandemic has made clearer than ever is that the people who make our society function—grocery store clerks, restaurant workers, sanitation workers, etc—have not been treated as they should. I hope that in the future people in these positions will get living wages, hazard pay, paid sick leave, etc. Also, I hope this drives home to people the need in this country for universal health care, brings the idea of a universal basic income into the mainstream political discussion, and teaches us to be better prepared.

Dr. Leverage: I think we are already seeing changes. Locally, a COVID-19 Mutual Aid Response group is operating via social media to enable connections within the community which match need with supply. People across the country are supporting local business when they can by buying gift vouchers for services and goods they might not be able to use immediately. As Dr. Rieux states at the end The Plague, “we learn in a time of pestilence [:] that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.”

Dr. Matei: One of the inadvertent products of the Black Death was Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353). This is a collection of at times light-hearted stories, with more than one accent of ribaldry, written as a form of literary consolation to the Black Death pandemic. At the same time, the religious establishment of the time focused on the opposite message, Memento Mori, or Live Your Life Saintly While You Can. Pandemics seem to induce an oscillation between “rejoice” and “repent.” Should we expect anything like it in contemporary popular culture?

Dr. Armstrong: I think we are already seeing a remarkable amount of artistic expression/response to this pandemic, and much of it may be characterized as an attempt to comfort, to entertain, and to connect with one another. The difference now is we get to see it more quickly, thanks to multiple media platforms, wifi connectivity, etc.

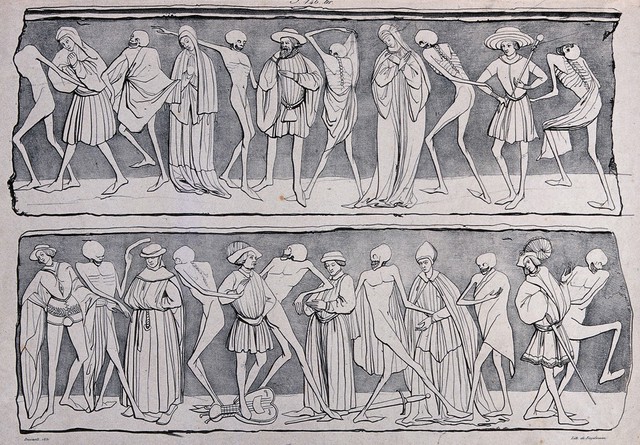

Dr. Leverage: I think it’s also useful to mention the Dance of Death, or the danse macabre tradition, which uncomfortably brings together the rejoicing with the less cheerful emotions. Thinking, too, about the popularity of different forms of art with different parts of society, the danse macabre is fascinating because it dramatizes Death leading figures from all stations of life into the dance of death. So, this tradition, represented in church murals, breaks down any possible perception that there is a divide between commoners and elite in their ultimate resistance to death.

Moving into the twentieth century, Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (1957) about the plague in medieval Sweden features an interesting scene set in a church during which Jons, the protagonist’s squire, strikes up a conversation with a painter decorating the walls with images of the Dance of Death. There follows a discussion about the purpose of art, the degree to which it should be realistic, and if it should aim to please. While Jons fears that the stark realism will frighten, anger, and render unhappy anyone looking at it, the painter insists that it will make people think.

Turning to contemporary popular culture, and COVID-19, three recent works have caught my attention: two by the British street artist Banksy (“Game Changer” in Southampton General Hospital and “Cupid with slingshot of roses”) in Bristol, and one by French artist Saype or Guillaume Legros (“Beyond Crisis”) in the Swiss Alps. Each of these works features a young child at play: in the first, a boy chooses a nurse superhero over more conventional superheroes from his toy box, in the second, a young girl launches a splatter of roses from a slingshot, and in the third, a girl sits holding hands in a circle of chalked stick figures. The earliest work of these three is the second, which appeared on February 14th. Immediately the disposition of the roses on the wall was compared to the coronavirus in its shape, and now retrospectively it would also appear to suggest airborne contagion. While the second has been read with the menace inherent in the emerging global crisis in February, the first and second appear to offer hope.

Dr. Matei: In times of crisis, such as this, the study or even the lessons of literature, art, or humanities, seem like luxuries, not necessities. However, the possibility of a global pandemic and its devastating effects was explored in movies, art, and literature almost to exhaustion in the last decades. In view of this, literature and film might not be the pursuit of imagining Things That Do Not Exist, but a very useful method to preemptively imagine that which Could Very Well Be. Literature and film might not be the esthetically distorting mirrors, but very effective forms of precognition (as in the movie Minority Report). How should we interpret the long series of pandemic movies, such as Virus, Pademic, World War Z, Outbreak, and so on, in view of this idea?

Dr. Armstrong: I think what most of those movies are about is less the actual pandemic than how people try to maintain or rebuild a society in the face of it. That’s what I find most interesting about them—what elements of civilization do we hold on to? Which ones do we let go or sacrifice? And obviously, different people have different priorities. Some people want to make sure that we protect one another and give our frontline medical workers time to get on top of the wave, and are willing to self-isolate for as long as necessary. Other people want to get back to normal and get a haircut. The whole spectrum of human behavior—from the utterly selfless to the extremely selfish—is on display.

Dr. Leverage: There are two perspectives on the question of literature and film at this time of crisis which we might usefully consider under the shorthand “reading the present through the past” and “reading the future through the past.”

The first informs the premise of the course I have been teaching this semester during the pandemic, The Middle Ages on Film. The directors of the films we analyze explore, through the lens of the Middle Ages, issues contemporary with the film’s production, such as AIDS / HIV, Muslim / Christian relations in the wake of 9/11, nuclear proliferation, the rise of fascism in Europe in the first part of the twentieth century, propaganda and censorship, etc. At the time when Purdue broke for Spring break, simultaneously with the announcement that we would return to online teaching, I had been discussing Bergman’s The Seventh Seal with my students in a section on the plague. Bergman’s film is ostensibly a “medieval” film since it engages with crusaders and plagues and flagellants, but it is more fundamentally a film about a quest for meaning at a time of existentialist crisis, with the protagonist Antonius Block desperately searching for evidence of the existence of God, and when he does not find that, he searches for one final act to give his life meaning before death. He finds this in helping the family of travelling players to escape.

When I adjusted the syllabus in response to the lockdown, I replaced the final exam with a project I called, “COVID-19 and the Middle Ages: The Director’s Project” which asked the undergraduates to consider the pandemic through the lens of the Middle Ages. As a director, how would they create meaning from this contemporary history through situating its representation in the Middle Ages? The final product could be an essay, a film, a film script, a short story, etc. This gave me a wonderful opportunity to see if they could apply their understanding of the concepts of the course to the historical circumstances through which they are living. The projects submitted by the students amazed me, and it was clear that it had been a useful exercise to think through their current experiences from the safe distance of the Middle Ages.

Credit: Christina Pansino, College of Liberal Arts / FVS Major. Project for LC333 The Middle Ages on Film (Spring 2020, Professor Leverage)

The second perspective, “reading the future through the past” is also one I can approach through recent teaching experience. In a Cornerstone course, I had already assigned reading from Albert Camus. After the pandemic came to town, I added Camus’s novel The Plague to the reading list, along with a project which asking the students to compare the psychological and institutional responses to the plague in the novel and COVID-19. Almost universally the response was incredulity that such a work could have been written which so accurately describes what we are experiencing, and that history repeats itself. Of course, Camus’s novel relates an outbreak of the plague in Oran, French Algeria in “194….” and not the Middle Ages, and has been read as an indictment of “la peste brune” or the rise of fascism in Europe. But what the students were recognizing was less the disease and contagion than the expression of human experience, as Camus describes in the book: “But the plague forced inactivity on them, limiting their movements to the same dull round inside the town, and throwing them, day after day, on the illusive solace of their memories. For in their aimless walks they kept on coming back to the same streets and usually, owing to the smallness of the town, these were streets in which, in happier days, they had walked with those who now were absent. Thus the first thing that plague brought to our town was exile.”

Dr. Matei: Any other thoughts about the drama of our pandemic experience?

Dr. Leverage: The relationship between the individual and community has sometimes been represented broadly as weighted more heavily towards community in the Middle Ages, with development towards an awareness of individual consciousness in the centuries that follow, and culminating in a contemporary Western society sometimes considered egocentric. COVID-19 has created circumstances in which recognizing the symbiosis of individual and community has become a critical public health issue. Masks and staying home symbolize self-serving altruism.

Dr. Armstrong: Just that I would really like to get off this ride now.